75. Booty from Byzantium: Part 4

Today I'm going to ask you to do something strange. I want you to feel sorry for an Emperor of Byzantium, a place which for most of its 1123 years of existence was the richest and most powerful empire the world had ever known. Nevertheless, I would like you to empathize with him and share for a moment what must have been for him a very painful experience.

Today I'm going to ask you to do something strange. I want you to feel sorry for an Emperor of Byzantium, a place which for most of its 1123 years of existence was the richest and most powerful empire the world had ever known. Nevertheless, I would like you to empathize with him and share for a moment what must have been for him a very painful experience.In 'Palazzo Dandolo' on May 31 in this blog, I told you how Venice sacked Constantinople, the capital of Byzantium, in 1204 and stole so many of its treasures. On June 16 and 17, and on July 10, I told you about the horses and the porphyry sculpture that Venice captured and has displayed ever since at the Basilica of San Marco. On July 7, I told you how Emperor John VIII Paleologus came cap in hand to Venice in 1438, imploring her help in defending what was left of his diminishing empire.

Imagine that scene in 1438. It is now 234 years after the sacking. Most of the wounds have healed. The Greeks under John VIII have been back in control of the Eastern Roman Empire again for 180 years or so. Trading has occurred. Venice and Constantinople are friends again. Well, sort of. John VIII arrives in Venice with his 600 strong entourage. He is housed in a large palace. He is treated with respect, welcomed with pomp and ceremony as an Emperor should be.

At some point during the sojourn, it is absolutely certain that the Doge would have invited his Imperial guest to worship with him at his private chapel. To not do so would have been disrespectful. To refuse would have been an insult. But this is the moment when the mighty power that Venice had become was able to psychologically crush its former master, and was able to do it passively, almost incidentally.

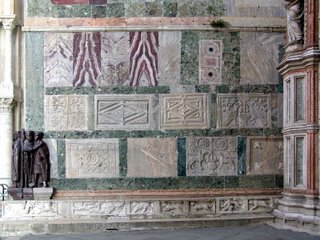

John VIII would not have walked to church from his palace on the Grand Canal. He would have ridden in an ornate vessel of some sort to the steps of the Doge's Palace, then walked, perhaps on a red carpet, the 100 meters or so to the Doge's own chapel – which just happened to be the Basilica San Marco – past this, the southern wall of the great church.

This image would have been the first part of San Marco that John VIII would have set eyes on. He would have known of and recognized the porphyry sculpture of his predecessors on the lower corner facing him, stolen from his home city. Perhaps he commented on it, perhaps he ignored it. Looking instead at the wall facing him, he would have seen slabs of marble and decorative panels that had once adorned the churches of Constantinople, now flaunted over every façade of the cathedral. Walking on, he would have looked up and seen the Quadriga horses from his own Hippodrome. Inside the church, in pride of place would have been the Palo d'Oro, a solid gold and jewel encrusted alterpiece containing dozens of Byzantine holy icons – all part of the booty boosted from Constantinople during the three days of rape and pillage following its fall.

Then, the ruler of Eastern Orthodoxy would have had to swallow even more of his pride and pray at a Catholic mass. His humiliation at the hands of his former vassal state would have been complete.

To his credit, the Emperor must have born his ignominious situation with dignity. Any other response would have surely been noted and recorded and gloated over.

But you have to feel a bit sorry for him. Don't you?

0 Comments:

Post a Comment

<< Home